Why Do Many Professionals Not Use AI Regularly?

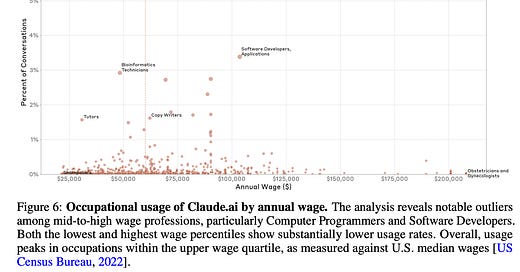

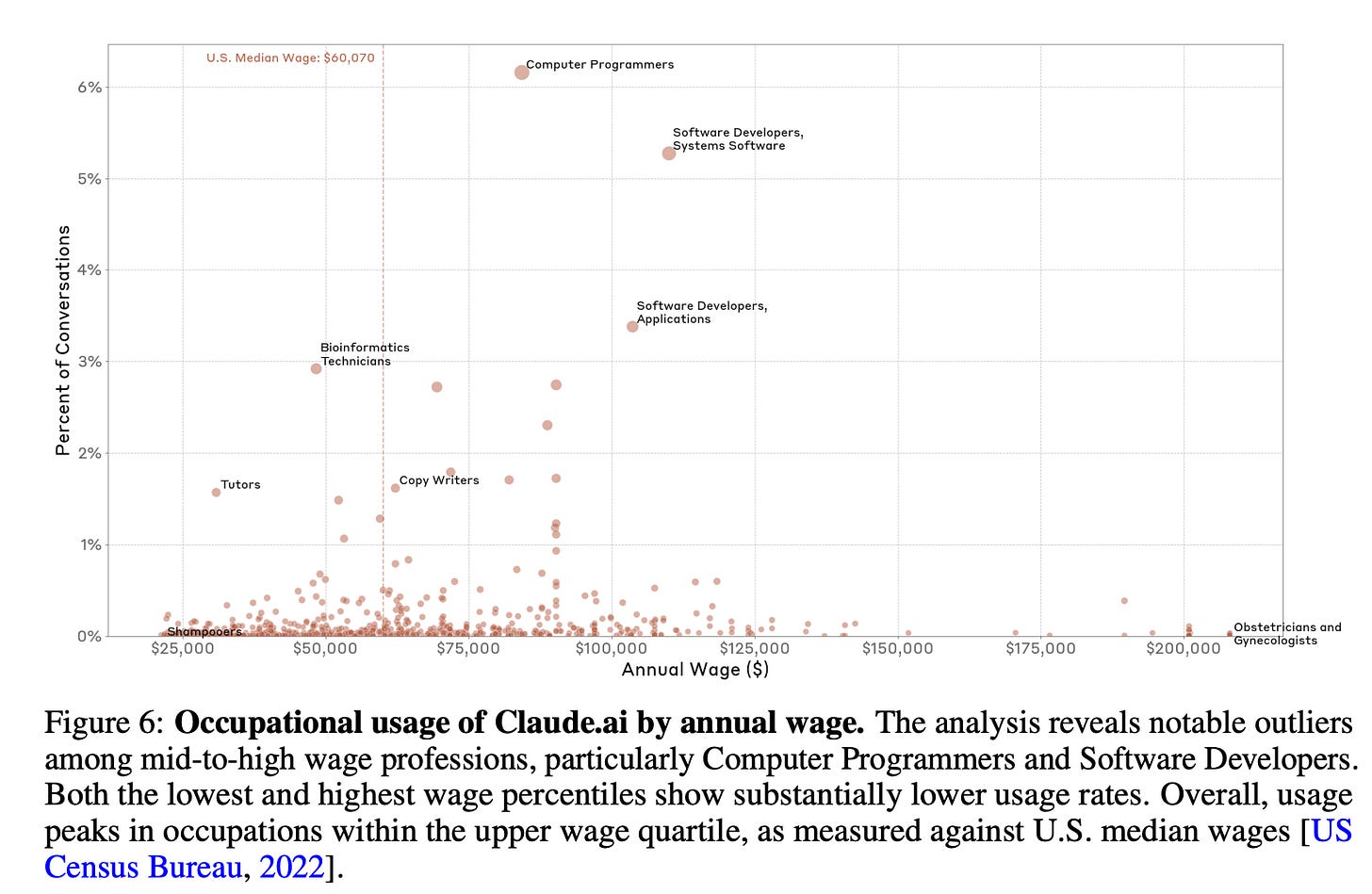

Many professionals do not use AI regularly. A recent paper from Anthropic noted that high-wage earners ($150,000+ annually), including management, physicians and lawyers, showed substantially lower usage rates of Claude.ai, Anthropic's AI tool, compared to those in mid-to-high wage professions. See Figure 6 of the paper.

CEOs and AI leaders, eager to see returns on their GenAI tools, often push for employee adoption without recognizing the social push and pull at play. Forcing AI use without addressing these contradictions risks alienating employees rather than empowering them.

So, why do many professionals not use AI regularly?

There's a strange social pressure around AI—both for using it and for avoiding it.

At my house, we constantly encourage our children to "ask ChatGPT" or "try Gemini". One day at the dinner table, my 11-year-old confessed that she only used AI 5-6 times last month. When I asked her why she didn't use AI more often, she hesitated: "AI has a bad rep. Ms. V asks us to submit the input and output for review if we use AI." My 16-year-old backed her up: "I can tell when something was written by ChatGPT. It is … bad."

The same paradox at my dinner table exists in many workplaces. In some teams, people who don't use AI are dismissed as being out of touch, while in others, people who use AI are seen as cheating or incompetent. It's entirely possible for someone to be encouraged to use AI in one setting and then discouraged from using it in another, all on the same day.

AI, as an outsider to many professions, has yet to prove itself.

Many professionals like lawyers take pride in our expertise, intuition, and ability to solve complex problems that machines simply can't grasp in the same way. We build our expertise over tens of years and gain our credibility over time. AI, no matter how advanced, lacks the lived experience, contextual understanding, and nuanced decision-making that define high-quality human work. And more importantly, general-purpose AI does not have the resume of a seasoned professional to be given instant credibility.

AI is an outsider–much like a healthcare CEO being appointed to run a retail conglomerate. While their skills may be transferable, they still need to learn from industry experts to be truly effective. Currently AI hasn't done enough to learn from human experts in many professions, including the field of law.

In my last blog, I shared how we used Deep Research tools to generate detailed research reports. When I shared the reports with other lawyers, some were impressed; others were skeptical: this AI sounds smart, but it doesn't know how the real world works. I agreed with them in part: legal advice from sophisticated human experts was more nuanced and risk-balanced.

Professionals want control over the creative and intellectual aspects of their work.

The reluctance to use AI often is not about the fear of change or old-fashioned thinking; it's about maintaining control over the creative and intellectual aspects of one's work. Good work isn't just about efficiency—it's about craftsmanship, judgment, and experience. AI might suggest a way to write an email, draft a contract, or analyze data, but that doesn't mean it understands the nuances that a human professional brings to the table. In addition, AI often comes across as "authoritative" even when the suggestions are wrong. For professionals who take pride in their expertise, this can feel condescending, intrusive, and counterproductive.

The decision of how and where to use AI is a personal one, and that choice is often not respected.

One of my colleagues was hesitant about using AI until one day he decided to ask AI a question that he had been trying to understand for years: What is time? He had an hour-long conversation with an AI tool and was amazed. When he told me how great the conversation was, I had no interest in replicating it myself.

This story tells me that, ultimately, the decision of how and where to use AI is a personal one, and that choice should be respected. It is one thing to see how other people are excited about AI; it is quite another to experience the excitement yourself. Needless to say, people are excited about different things.

So instead of asking professionals to take a leap of faith in AI, I am offering the following ideas:

Don't get stuck in other people's use cases.

Professionals value control over the creative and intellectual aspects of their work. That's why it's important to start where it makes sense for you—not where others say AI should be used. If you're highly skilled in a particular area, you may resist AI's involvement there, and that's okay. For example, if you're a proficient writer, you might not want AI to help you write—but you might be open to using it for drawing, brainstorming, or analyzing data.

AI isn't an all-or-nothing tool. Instead of forcing it into areas where you already excel, experiment with it in domains where you're still learning or curious. Use it as a tool to expand your skills, not just to automate what you already do well.

Discover your 'Goldilocks Zone'.

After 25 years of practicing law, I can't look at a document without instinctively making edits. AI has become an integral part of my drafting process, unleashing my creativity and productivity in ways I never imagined. However, on average, I revise 70% of AI-generated content. This "70% rule" has become my personal operating model, helping me overcome the fear of being seen as cheating or lazy.

But 70% isn't a magic number—it's just what works for me. Your 'Goldilocks Zone' may be different. The key is to strike a balance so you stay in control. Recently, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) confirmed that human authors are entitled to copyright in their works of authorship that are perceptible in AI-generated outputs, as well as the creative selection, coordination, or arrangement of material in the outputs, or creative modifications of the outputs. Similarly, the use of AI tools does not negate the patentability of an invention where humans make significant contributions.

Shift the mindset from using AI to delivering quality work at speed.

Rather than focusing on whether to use AI, professionals can focus on how to deliver high quality work products at speed. No one wants to risk overlooking a critical issue in a contract, but at the same time, a stalled contract can sink a deal. Doctors can't afford oversights by relying on AI-generated outputs, however, a delayed diagnosis can cost lives. There is a hidden cost of delay that is often overlooked.

In the past, managing the trade-off between quality and speed was difficult, if not impossible. Generative AI offers a new possibility: the ability to enhance both simultaneously. As an AI leader and CEO, the job isn’t just about adopting new technology—it’s about guiding professionals in managing the trade-off between quality and speed in the new AI-powered world and being accountable for the decision. Speed alone isn’t enough; neither is accuracy in isolation. The new standard must balance efficiency, reliability, and human expertise, ensuring that AI enhances work rather than diluting its value.

Conclusion

The future of AI isn't about forcing everyone to use AI but about setting a new standard for high-quality work at speed. AI isn't a one-size-fits-all solution: the decision of how to use AI is a personal one, and that choice should be respected. The real success of AI will be measured not by how many people use it, but by how well it enhances the work of all. If you are ready to give AI a try:

Start with an area you want to learn more about instead of the one you already have deep expertise in.

Discover your 'goldilocks zone' of how much you should modify AI-generated content.

Stay in control of the outcome and strive for not only high quality but also speed.